Safferz

-

Content Count

3,188 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Posts posted by Safferz

-

-

Thanks everyone!! Nice to be back on the forums, it's been a minute

-

1

1

-

1

1

-

-

I went there during the soft opening in June and it was great. Good food and good vibes. But I'm pretty sure Jamal is the chef and based in NYC now, not that he came in from MN to consult.

-

Saalax, is it difficult to travel there from Hargeisa? Did they finish building the road to Ceerigaabo yet?

-

<cite>said:</cite>Yes exactly.I'll say this though. I've never seen anything like your twitter/FB/Web campaign(or should I say onslaught:) against SJAS. I think you can legitimately claim you're the first Somali to do that type of thing.

haha! I tapped into a much longer tradition of Somali qarxis for that though, so I can't say I'm a first

I've actually been thinking about trolling and starting a Tumblr or something called Somali Firsts. First Somali to fadhi ku dirir, first Somali to chew qat, etc.

-

<cite>said:</cite>Interesting story. I find it fascinating he said he believes he is the first one. His story is unusual enough that it wasn't necessary to add a tidbit that can't be verified or refuted. Somalis and the trailblazer mentality.Somalis always declare they're the first to do something. I'm sure there are half-Somali Chinese citizens out there, given so many Somalis have gone to China for school, training, etc since the 60s.

-

-

lol! Interesting article. I was really surprised to read only 85 of the UK’s 18,500 professors are black.

-

It's refreshing not to see this thread in the "women" section

-

An apartheid state founded on settler-colonialism is racist to non-white Jews too, shocking

-

<cite>said:</cite>This must be a job offer from Harvard Safferz. I am I right?No, not at all! Just the interest, funding and support/institutional commitment to bring this discussion to Harvard. It would be bringing everyone interested in developing this theoretical intervention and new line of inquiry/future directions for scholarship in one place, and following it up with a published collection of the essays they present there. The professors here have all been following closely and have been incredibly supportive.

-

Thanks Galbeedi

I thought this event was terrific. One other dynamic of this social media moment has been democratizing academia in some way -- instead of limiting debates to the pages of academic journals no one reads, we are seeing conversations about Somali Studies taking place everywhere.

I thought this event was terrific. One other dynamic of this social media moment has been democratizing academia in some way -- instead of limiting debates to the pages of academic journals no one reads, we are seeing conversations about Somali Studies taking place everywhere. -

<cite>said:</cite>Yet, this type of scholarship does not encourage the African to correct these prejudices with an actual counter-study. Instead, it tells the African that he--because of his sheer Africanness--knows better. That he is more privileged to speak on the topic because he is the subject of study.The insidious aim of those who encourage this type of study is a slow unraveling of actual scholarship which culminates in a form of censhorship. That is why we see the subject resort to a form of name-calling and label certain studies as products of the "colonial gaze" or "racist" or "misogynist." The subtle aim is to discourage debate and dismiss certain efforts as motivated by sheer prejudice. It is to reserve a certain area for study for a specific group because they are part of that studied group.I do not disagree with its utility as a preface to an academic work. But it cannot be scholarship by itself. It is lazy. It is territorial. And it is perpetuated by personal attacks. But most importantly, it is a way for the inferior, the subject of a prejudicial study to express his rage.All the while the master smiles. Because when history is read, it will say--"the African is a savage because of x, y, z." And African's response will be "that scholar is racist because he said x, y, z and it doesn't apply to me."The proper response should be--"the African is not x, y, z, rather he is a, b, c."I don't think you read the article, because I'm not sure how else you'd essentialize and reduce my argument to this or suggest that we are not doing research. Everyone here on SOL knows that I spend months in Ethiopia doing fieldwork and archival research, and that I return each year for research while I work on my dissertation. I am not sure where your suggestion that I/we are not also academically productive is coming from. Furthermore, theory, critique and deconstruction are critical aspects of academic work -- they shape and reshape the paradigms within which scholarship is then produced. We have to analyze and critique the politics of knowledge at the same time that we produce, the two are inextricably linked.

Nowhere have I said that non-Somalis should vacate the field of Somali Studies or that Somali Studies is reserved for Somalis. What I'm trying to do is highlight the systems of power embedded in the production of knowledge ABOUT Somalis and the Somali region, which also operates to marginalize the Somali within knowledge production and position and sustain the Western researcher as expert. This is about systems, not individual researchers. My article traces this history of power and gestures towards the futures and possibilities for a new Somali Studies. The space to do this work is now there. This is a major ontological and epistemological intervention for Somali Studies, and these conversations fit within a larger intellectual intervention made by postcolonial studies (Edward Said, Subaltern Studies, etc).

You guys can dismiss me if you'd like, misread my arguments as Somali essentialism and "nac nac iyo hadal," that's fine. I know it's not, and major academics around the world have recognized it too. The fact is that I had a specific goal in this - to make an intellectual intervention in Somali Studies as an academic field as an academic who does work in this field - and I have done that and will continue to do that theoretical work in tandem with my historical research. Harvard has even insisted that it be the place to host conferences to theorize this new Somali Studies, and I have other projects underway.

-

-

<cite>said:</cite>Bravo Safferz!"The Decolonising Our Minds Society"? Is that a new group?I believe they're a student group based at SOAS, not sure how long they've been around. I watched the video and it's an interesting mix of people, not only graduate and undergraduate students but professionals and other concerned members of the community (Somali and non-Somali). I was told it would be a panel when I was asked to record a message, but I love how they did it more as a townhall style discussion. Looking forward to watching the other videos from the discussion once they're up!

Here are the live tweets from the discussion: https://storify.com/HajiKenadiid/can-the-somali-speak-roundtable-discussion-soas-on

-

<cite>said:</cite>I didn't read the comments but from get-go, his argument seemed personal. It was hardly an objective criticism. It looks like you have ruffled a few feathers.I chuckle a bit when I hear someone say 'I am not [insert];...He seems to have had a difficult time with Somalis as a Ugandan doing research there, and thinks his experience is analysis. That, combined with misreading my argument, leads to this.

-

He actually shopped this piece around to a number of more academic sites who refused to publish it because he fundamentally misreads postcolonial studies as well as the argument I'm making. But in order to 'reply' to me, he has to make me say things I haven't said.

The comments in the comment section are great. I think this one nails it:

Yusuf Serunkuma's essay is a very insincere piece of writing. It also deliberately misunderstands the issues at stake in Cadaan Studies and in Safia Aidid's essay in the New Inquiry. Whiteness in Aidid's essay is referring to a system of power that could also be framed as Eurocentric, but where a history of racialization stands at its centre. Aidid is less concerned with individual prejudice. Serunkuma's essay also contradicts itself when it tries to discount Aidid's efforts by claiming that the problem of Somali Studies is the problem of African Studies more generally. If this is true, what stops someone from specifying how whiteness works specifically within Somali Studies? Moreover, Aidid's essay is not an attempt to racially profile anyone, rather, Aidid's project simply calls for a genealogy of power within Somali Studies. In no way is Aidid trying to call for more objective studies. Within African Studies she follows a research methodology best developed by Mudimbe in his book, The Invention of Africa. The point is to self-reflexively critique the ways power shapes knowledge production. This is the opposite of a call for more objectivity, but at the same time it is not a slip into endless relativism. Systems of power exist, part of the scholarly legacy of thinkers such as Said or Chatterjee is to show why questioning these systems are a legitimate part of inquiry into all aspects of Area Studies.All that said, I'm not Markus and I don't believe in singular narratives. The point is to open up critical space for multiple critical perspectives, even ones that misunderstood #CadaanStudies and my essay, and I think we've done that.

-

<cite>said:</cite> I know Safferz would be laughed out of any University lecture hall with this nonsense she's trying to sell to the Somali community.This is academia. No one cares about your racial origin in the academic world. Either you compete or you sit down. If you can't handle the heat, then maybe you should have chosen a different career path.Let's review the non-Somali academics who are in support of the #CadaanStudies critique:

- Allison Taylor, PhD Brandeis, sociocultural anthropologist

- Sean Hawkins, Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Toronto

- Antoinette Handley, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, University of Toronto

- Rima Berns-McGown, Associate Director, Centre for the Comparative Study of Muslim Societies and Cultures, Simon Frasier University

- John Comaroff, Professor of African and African American Studies and Anthropology, Harvard University

- Jean Comaroff, Professor of African and African American Studies and Anthropology, Harvard University

- Laura Correa Ochoa, PhD Student in History, Harvard University

- John Gee, PhD Candidate in History, Harvard University

- Rita Nketiah, PhD Student in Women's Studies, University of Western Ontario

- Tshweu Moleme, Political Science researcher, Munk School at the University of Toronto

- Rachel Thompson, PhD Candidate in Anthropology, Harvard University

- Juliane Okot Bitek, poet and PhD Candidate in Interdisciplinary Studies, Liu Institute for Global Issues, University of British Columbia

- Ryan Kelpin, MA Political Science at York University and Executive DIrector, Cities First

- Kelly-Mae Saville, Student Chair for Sociology and Policy, Aston University UK

- Tendisai Cromwell, writer and filmmaker

- Sakinah Hasib, student, University of Waterloo

- AFRICA IS A COUNTRY

- Binyavanga Wainaina, writer

- Melissa Finn, Lecturer in Political Science, Wilfrid Laurier University

- Erin MacLeod, PhD, Lecturer, University of West Indies, Mona Campus

- Jasmine Zine, Associate Professor of Sociology, Wilfrid Laurier University

- Elleni Centime Zeleke, Lecturer and PhD Candidate, Social and Political Thought, York University

- Amber Young, Graduate Student, Social Work, University of Calgary

- Harry Verhoeven, Assistant Professor at Georgetown University, Associate Member of Department of Politics and International Relations, Oxford University, Convener of Oxford China-Africa Network

- Yolande Bouka, PhD, Researcher, Institute of Security Studies Nairobi

- Bethlehem Seifu Belaineh, student, activist, community organizer and Racial Minority Senator, Brandeis University

- Rowa Mohamed, University of Western Ontario

- Tracian Meikle, PhD Candidate, Department of Geography, Planning, and International Development, University of Amsterdam

- Benjamin Dix, PhD Candidate in the Anthropology of Violence, Director of PositiveNegatives

- Kariima Ali, BSc Psychology, Goldsmiths University UK

- Netta Kornberg, Research Assistant, Faculty of Education, York University

- Juliane Hammer, Associate Professor, Department of Religions Studies, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill

- Denise Spitzer, PhD, Canada Research Chair, University of Ottawa

- Caroline Elkins, Professor of African and African American Studies and History, Harvard University

- Monica Fagioli-Ndlovu, PhD Candidate in Anthropology, The New School for Social Research

- TRANSITION MAGAZINE

- Mulugeta Hailemariam Zegeye, BA Addis Ababa University, MSc University of Glasgow, Former Member of Ethiopian Parliament (Chairman of Budget Committee) and Fmr Chairman of Ethiopian Athletics, African Languages Program, Harvard University

- Jamilla Davis, student in Anthropology and Educational Studies, Bates College

- Hawa Noor, writer, BA International Relations and African Studies, University of Toronto

- Jacqueline Russel, MA, Health Research Specialist, Toronto Public Health

- Sarah Kennedy Bates, PhD Candidate in History, Harvard University

- Alemayehu Weldemariam, former Professor at Suffolk University, graduate studies George Mason University

- Nakanyike Musisi, Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Toronto

- Yannick Marshall, poet, PhD Candidate, Middle East, South Asian, and African Studies, Columbia University

- James J.T. Roane, PhD Candidate in History, Columbia University

- Axelle Karera, PhD Candidate in Philosophy, Penn State University

- Tiffany Tsantsoulas, PhD Student in Philosophy, Penn State University

- Ricky Varghese, PhD, RSW, psychotherapist, art critic and writer, University of Toronto

- Kathy Kiloh, PhD, Instructor, OCAD University

- Vasuki Shanmuganathan, PhD Candidate in German and Women and Gender Studies, University of Toronto

- Ajamu Nangwaya, PhD, Instructor, Seneca College

- Rachael Hill, PhD Candidate in African History, Stanford University

- Lena Weber, MSc Candidate in Human Ecology, Lund University Sweden

- Bhakti Shringarpure, editor-in-chief Warscapes Magazine and Assistant Professor, University of Connecticut

- Hillina Seife, PhD Candidate in History, University of Michigan

- Natasha Issa Shivji, Lecturer, Department of History, University of Dodoma, Tanzaniaand PhD Candidate in History, New York University

- WARSCAPES MAGAZINE

- Natasha Obiri, blogger, BA History and Philosophy, University of Toronto

- Keguro Macharia, Independent Scholar, Nairobi

- Stephanie Belmer, PhD, Instructor, Vanier College

- Kay Kaufman Shelemay, G. Gordon Watts Professor of Music and Professor of African and African American Studies, Harvard University

- Alessandra Di Maio, Associate Professor, Department of Humanities, University of Palermo, Italy

- Efe Levent, National Chiao Tung University, PhD Institute of Applied Arts

- Andrew Pope, PhD Candidate, Harvard University

- Chambi Chachage, PhD Candidate, Harvard University

- THE AFRICA COLLECTIVE

- Andreas Admasie, PhD Candidate, University of Basel

- Alula Eshete, MBA Candidate, Harvard Business School

- Molefi Kete Asante, Professor, Temple University

- Molefi Kete Asante Institute for Afrocentric Studies

- Afrocentricity International Inc.

- Maxi Schoeman, Professor and Head of Department of Political Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa

- David McGraw Schuchman, MSW, LICSW, Clinical Social Worker, Minneapolis

- Michael Busch, Senior Editor of Warscapes Magazine, and Doctoral Candidate in Political Science, The Graduate Center, CUNY

- Aaron Bady, Postdoctoral Fellow, University of Texas, Austin

- Alexandra Berceanu, MA Communications & Culture, Ryerson University

- Moyosore Arewa, student, Wilfred Laurier University and Opinion Editor, The Chord

- George Brooke-Smith, BSc Philosophy, Politics and Economics, University of York

- Sinthujan Varatharajah, PhD Candidate in Political Geography, University College London, University of London

- Meghan Healy-Clancy, PhD, Lecturer on Social Studies and on Women, Gender and Sexuality, Harvard University

- Jeremy Rich, PhD, Chair, Social Sciences Department, Maywood University

- Karen Larbi, BA Hons, Law and Social Anthropology, SOAS, University of London

- Azeezat Johnson, PhD Student in Geography, University of Sheffield UK

- Jill Kelly, History, Southern Methodist University

- Bilal Zenab Ahmed, PhD Student, SOAS, University of London

- Arman Osmany, MA Comparative Literature, King's College London

- Jonathan Paul Katz, MSc Student in Migration Studies, University of Oxford

- Keren Weitzberg, PhD, Postdoctorate Researcher, Joseph H. Lauder School of Management and International Studies, Department of History, University of Pennsylvania

- Nadiya Ali, PhD Candidate, SOAS, University of London and Co-Founder, Indigenous Insight-Africa

- MJ Rwigema, PhD Student in Social Work, University of Toronto

- Jonathan Paul Katz, MSc Student in Migration Studies, University of Oxford

- Sarah Nwafor, African Studies, University of Birmingham

- Jessica Cammaert, PhD, Sessional Lecturer, Department of Global Studies, Wilfrid Laurier

- Kabita Chakraborty, Assistant Professor, Children's Studies, Humanities LAPS, York University

- Elisabeth Gade, MA Student, University of Oslo, Norway

- Nathaniel Matthews, PhD Candidate, Northwestern University

- Gatete TK, LLM Human Rights and Democratisation of Africa, University of Pretoria

- Shireen Ahmed, writer and sports activist

- Joakim Gundel, Political Analyst, Katuni Consult

- Robin Turner, PhD, Associate Professor of Political Science, Butler University

- Anni Movsisyan, BA Mixed Media Fine Art, University of Westminster UK and Activist

- Kim Yi Dionne, Assistant Professor of Government, Smith College

- Gurminder K. Bhambra, Professor of Sociology, University of Warwick UK

- Jasmine Gani, Lecturer, School of International Relations, University of St.Andrews

- Wossen Ayele, JD Candidate, Harvard Law School

- Emmanuel Akyeampong, Professor of History and African and African American Studies, Harvard University

- Rannveig Haga, Postdoctoral Researcher, Södertörn University College

- Simmi Dullay, Black Consciousness Decolonial Scholar and Cultural Producer

- Marcia Lynx Qualey, ARABLIT e-magazine

- Stephanie Lämmert, PhD Student in History, European University Institute

- Nishi Singh, MA Candidate in Globalization Studies, Institute on Globalization and the Human Condition, McMaster University

- Ylva Habel, Assistant Professor, Media and Communication Studies, Department of Learning and Communication, Södertörn University Sweden

- Uros Zver, Department of History and Civilization, European University Institute Italy

- Sara Ahmed, Professor of Race and Cultural Studies, Goldsmiths, University of London

- Muneer Karcher-Ramos, Community Faculty, University of Minnesota

- Tommaso Giordani, Doctor in History and Civilization, European University Institute, Florence

- Silvan Heinze, Student of Area Studies, Humboldt University of Berlin

- Monica J. Casper, PhD, Professor and Head, Gender and Women's Studies, Affiliated Faculty in Africana Studies & School of Sociology, University of Arizona

- Stephanie Latty, PhD Student, Social Justice Education, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

- Dylan Lambert-Gilliam, Student of Global Studies, University of California, Santa Barbara

- Aili Tripp, Professor of Political Science and Gender & Women's Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Angela Last, PhD, School of Geographical and Earth Sciences, University of Glasgow

- Jesse Mills, PhD, Associate Professor and Chair of Ethnic Studies, University of San Diego

- Brian Kwoba, PhD Student in History, Oxford University and organizer of Oxford Pan-Afrikan Forum

- THE FEMINIST WIRE

- Marta Kozlowska, PhD Candidate and Research Associate at the Institute of Sociology, Faculty of Political and Social Sciences, Freie Universität Berlin

- Rahma Bavelaar, PhD Candidate in Anthropology, University of Amsterdam

- Anna Hermanson, MSc Candidate, Lund University

- Steven Mageri, Graduate Student, Colin Powell School for Civic and Global Leadership

- Kassahun Checole, Publisher, Africa World Press Inc., Red Sea Press Inc

- Danielle Provencher, MA Candidate, University of Ottawa

-

-

Overinflating your own importance

Perhaps when you present material, ideas, points, etc - if you can - we can engage in a discussion. But you haven't said anything here.

Perhaps when you present material, ideas, points, etc - if you can - we can engage in a discussion. But you haven't said anything here. -

Neither of you make points, let alone valid ones. I'm involved in things much bigger than debating undereducated trolls on SOL who have nothing important to contribute to the topic.

-

<cite>said:</cite>@Safferz, are you after the truth or sheeko? There's barely any "rigid methodological empiricism" in the social sciences of Somali studies. Anthropology, and its subfields, are the closest.Subjectivity, and postcolonial critiques are luxuries. Empiricism is not. It is in fact, more sorely needed today by an audience that is vulnerable to tribal, black or arab solidarity biases etc.This is a really boring, thoughtless reply. It's clear the article went over your head and you are unfamiliar with the social sciences and their history.

-

-

What would a decolonized Somali Studies look like?

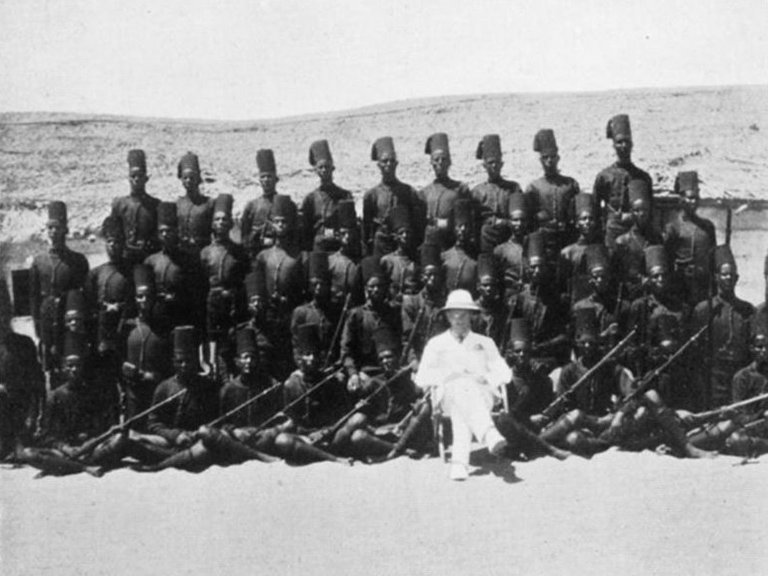

Since #CadaanStudies was launched on Twitter, the tweet that has received the most circulation has been something that British explorer Sir Richard Francis Burton wrote in his 1856 travelogue First Footsteps in East Africa:

Burton had arrived in Zeila, his first stop before traveling through the rest of Somaliland and the broader Horn of Africa. He was keenly interested in the culture, beliefs, and practices of the curious “Somali race” that he encountered, and he discovered many things about them. He discovered, for example, that the Somalis of Zeila in 1856 believed that fever was connected to mosquito bites, and he speculated that this “superstition probably arises from the fact that mosquitoes and fevers become formidable about the same time.” He also re-discovered what he already knew: that the difference between “superstition” and “fact” could be traced along racial lines and that knowledge and thought was the realm of the European.

It would not be until 1880 that a French doctor, Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran, would discover the malaria parasite in Algeria, for which he would win the Nobel Prize. Finally, in 1897, a British medical officer in British India, Ronald Ross, would be credited with discovering that malaria was indeed carried by mosquitos.

Burton’s condescension still characterizes the encounter between European and Somali. When ethnographic observation was crystallized as a methodology and a science, only Europeans were seen as capable of the rigorous analysis, reason, and knowledge production it required. Somalis existed only as the backdrop for their intelligence and understanding, as superstitious, irrational, unsophisticated, and unscientific.

#CadaanStudies explores the ways in which these colonial epistemologies continue to be the foundation of the field of Somali Studies. It began in response to the total absence of Somali academics and researchers from the editorial and advisory boards of the newly launched Somaliland Journal of African Studies (SJAS), which claimed to have been founded in collaboration with the University of Hargeisa, since deniedby the university. But the hashtag exploded after a member of the advisory board, Markus Hoehne, made his own observations about Somalis:

I did NOT come accross [sic] many younger Somalis who would qualify as serious SCHOLARS – not because they lack access to sources, but because they seem not to value scholarship as such. Sorry to say, but to become a successful political scientist, social anthropologist, sociologist or human geographer, you study many years without an economically promising end in sight. You have to work hard before you get out one piece of text and even then, you often get more criticism than praise. You certainly do not become rich quickly as a social scientist, at least if you have to pay your bills in Europe or Northamerica.Now, where are all the ‘marginalised’ Somalis who do not get their share in academia? I guess you would have to first find all the young Somalis who are willing to sit on their butt for 8 hours a day and read and write for months to get one piece of text out. Okay, before you ‘crucify’ me now for my neo-colonial racist male writing, I ADMIT that given the lack of good quality higher education in social sciences INSIDE Somalia, one cannot enter into a fair competition between cadaan iyo madow [white and black] scholars here. BUT, there are many young Somalis in UK, USA and continental Europe who have a chance to get a degree from a well-established university in social sciences and become master analysts of Somali and other affairs (where are Somali sociologists who work on issues of discrimination or inequality in the USA or Europe, where are Somali religious scholars who engage in the debate about Islam in Europe? Sometimes you have to look beyond your Somali navel). But in my life, I met only very FEW diaspora Somalis who seriously pursued such a career (in social sciences). So, your activism is good, but what you actually would have to do – instead of getting outraged at cadaan scholars, is to sit down and get your analysis out and criticise not cadaan for writing sth, but your own brothers and sisters for not writing better stuff!

I did NOT come accross [sic] many younger Somalis who would qualify as serious SCHOLARS – not because they lack access to sources, but because they seem not to value scholarship as such. Sorry to say, but to become a successful political scientist, social anthropologist, sociologist or human geographer, you study many years without an economically promising end in sight. You have to work hard before you get out one piece of text and even then, you often get more criticism than praise. You certainly do not become rich quickly as a social scientist, at least if you have to pay your bills in Europe or Northamerica.Now, where are all the ‘marginalised’ Somalis who do not get their share in academia? I guess you would have to first find all the young Somalis who are willing to sit on their butt for 8 hours a day and read and write for months to get one piece of text out. Okay, before you ‘crucify’ me now for my neo-colonial racist male writing, I ADMIT that given the lack of good quality higher education in social sciences INSIDE Somalia, one cannot enter into a fair competition between cadaan iyo madow [white and black] scholars here. BUT, there are many young Somalis in UK, USA and continental Europe who have a chance to get a degree from a well-established university in social sciences and become master analysts of Somali and other affairs (where are Somali sociologists who work on issues of discrimination or inequality in the USA or Europe, where are Somali religious scholars who engage in the debate about Islam in Europe? Sometimes you have to look beyond your Somali navel). But in my life, I met only very FEW diaspora Somalis who seriously pursued such a career (in social sciences). So, your activism is good, but what you actually would have to do – instead of getting outraged at cadaan scholars, is to sit down and get your analysis out and criticise not cadaan for writing sth, but your own brothers and sisters for not writing better stuff!

Cadaan means “white” in Somali, and the hashtag #CadaanStudies gestures towards the conceptual whiteness of knowledge production in Somali Studies. It is an analysis of the systemic and the normative positions and relations it produces. It is a way of thinking about the words of one anthropologist and the exclusions of one journal not as isolated incidents, but as signifiers of the current state of Somali Studies, and the ways in which it has continued to sustain non-Somali dominance on all things Somali. It examines how colonial logic is replicated in contemporary scholarship on Somalis, and in the research practices of non-Somali academics in their gaze upon the Somali.

Hoehne’s comments offer a unique moment of revelation, but also a window of insight into banal systems of everyday power. They show a mindset in which the Somali is rendered passionately partisan, while the non-Somali researcher remains worldly and detached in his analysis. They highlight a perception of Somalis as too steeped in their Somaliness to objectively assess their own reality. They reveal an understanding of us, the detribalized, tweeting natives of the Somali diaspora, as rebellious, overly emotional and insulting towards the cadaan scholars with which he identifies. They expose the view of Somalis as fundamentally lazy, requiring the non-Somali anthropologist to explain how we can overcome our undisciplined nature through the hard work that we are currently, sadly, incapable of.

As with Burton and the malaria-carrying mosquito, for a European to be unaware of information articulated by Somalis does not indicate his own ignorance. How could it? Somali beliefs are not facts.

The First International Congress of Somali Studies was held in Mogadishu in July 1980; the Somali Studies International Association, which had been founded two years earlier, “sought to promote scholarly cooperation and collaboration in investigations and interpretations of Somali society, culture and habitat.” But while this multidisciplinary sub-field of African Studies was institutionalized in the 1980’s, its origins are during the colonial period, when academic interest in Somalis first emerged alongside and within the colonial project. Some of the scholars in attendance at the 1980 Congress had begun their research on Somalis during the colonial era, starting with British anthropologist I.M Lewis, often called the founding father of Somali Studies.When Lewis passed away, in 2014, his obituary began by drawing a line right back to Burton: “Professor Ioan Lewis, the founding father of Somali studies, dedicated his life to studying a people described by the 19th-century explorer Sir Richard Francis Burton as “fierce and turbulent”, and a country viewed as a serial failed state.”

Somali Studies was established as a subfield and organization in a time of great intellectual ferment. Publications like Edward Said’s Orientalism and Michel Foucault’s History of Sexuality were in wide circulation by 1980, as were the ideas of Antonio Gramsci, particularly after Raymond Williams began to bring Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks to Anglophone audiences. E.P Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class had spurred on a variety of new social histories “from below” throughout the 1970s, challenging older, state-centered approaches; by 1979, women’s history had emerged as a field and gender would soon be theorized as an analytical category signifying relations of power in society. Subaltern Studies: Writings in Indian History and Society was launched in 1982, seeking to write histories outside of colonial constructions of knowledge and power.

It was a period of deconstruction and interrogation, of theory and reflexivity. But it did not touch Somali Studies.

Behind all of this new thinking was the decolonization of former European colonies, including the Somali territories. Nationalism and independence had created an epistemic crisis for anthropology, as the discipline grappled with its colonial origins and its focus on so-called “primitive” societies. Talal Asad and others challenged the truth of ethnographic representation and the discipline’s claims to scientific objectivity, enabling ethnography to be rethought as interpretation rather than scientific fact, and to critique its roots in colonial rule. The postmodern turn of the 80s and 90s and an increasing concern for reflexivity and subjectivity further reshaped anthropological praxis: the discipline now engages with the question of power dynamics, representation, and the ethics of research. All of this was necessary for the discipline to have future in a postcolonial world.

I.M Lewis began his fieldwork in the 1950s in British Somaliland, funded by the Colonial Social Science Research Council. His analysis of the Somali clan system—first published in his 1961 book A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa —continues to dominate understandings of Somali political and social life, despite its flaws. It reduced the complexity and heterogeneity of Somali society as a whole to a monolithic, nomadic pastoralism even though it was based on his fieldwork observations in only one region of Somaliland. His research was firmly embedded in an older tradition of British anthropology and worked to create the fiction of a self-reproducing Somali society, rooted in a rigid kinship system and with traditions unaffected by historical process. It made little sense to ask how clan is a product of modernity and subject to historical process, because Somali society was seen as primordial, outside of history and isolated from the world. He assessed Somali tradition in a vacuum, as though culture and tradition were not being transformed as Somalis were drawn into colonial regimes and a global capitalist economy, the very historical moment that enabled Lewis’ anthropological research in the first place.

He applied his framework to observe the Somali civil war 40 years later: “The political geography of the Somali hinterland in 1992, consequently, closely resembled that reported by European explorers in the 19th century, spears replaced by Kalashnikovs and bazookas.”

A volume of essays on Somali culture, society and politics co-edited by Markus Hoehne and Virginia Luling, which reviewer Gunther Schlee described as a compilation of the “Who’s Who in Somali Studies,” was published in honour of Lewis’ eightieth birthday in 2010. Essay submissions deemed too critical of Lewis did not make it to final publication.

#CadaanStudies marks a departure from the older and more rigid methodological empiricism of the social sciences that has dominated Somali Studies from its colonial beginnings, and a long overdue move towards theory, subjectivity and postcolonial critique. The social sciences were born in a particular moment of European modernity, resting on concepts like the nation-state that have since taken on new forms in our postcolonial, globalized world. Nowhere is this more evident than in the Somali territories, which have undergone radical shifts in the new global order. To read them through a colonial-era lens is to close our eyes to what is there. New sovereigns, forms of governance, and political subjectivities have emerged in the aftermath of civil war, within and beyond the collapsed nation-state, as the Somali territories have become contested ground for world historical processes of capital and modernity, and a vantage point from which to gaze back upon the West and deconstruct broader systems of power, including that of knowledge production.

What would a decolonized Somali Studies look like? You can see glimpses of it in the imaginative scope of research conducted by the many young Somalis whose names appear in the collective response to SJAS and Markus Hoehne. Yusuf Dirie engages with subalternity and examines how Western notions of modernity and progress informs debates on pastoralism in the Horn of Africa. There is the reflexive ethnography of Ahmed Ibrahim in his anthropological study of the local production of Islamic orthodoxy in southern Somalia. There is my own research on the affective and imagined geographies of modern Somali nationalism in its historical interaction with the Ethiopian state. Ilyas Abukar intervenes in practices of diaspora and Somali manifestations of blackness among refugees in the United States. Hawa Y. Mire uses art and storytelling to theorize agency and show the multiple ways that Somali women subvert patriarchal discourse.

#CadaanStudies has revealed a Somali Studies in crisis, trapped within a colonial imaginary in a postcolonial, postmodern world. What started as social media discussion has opened up a new space for thinking and theorizing about Somalis, the Somali territories, and the world they inhabit. Its significance will be its call to reimagine the conceptual apparatus of the field, focusing on the systemic level and how it has come to shape academic knowledge production about Somalis and the Somali region. Somali-produced scholarship will be central to academic knowledge, and #CadaanStudies is a disjuncture from which we can begin to theorize and develop new languages and methodologies to describe, analyze and understand new processes, systems, and ways of being. It is time to reimagine a Somali Studies for the postcolonial moment.

Safia Aidid

Safia Aidid is a PhD Candidate at Harvard University.

Safia Aidid is a PhD Candidate at Harvard University.Her research interests include modern Northeast Africa (Somalia and Ethiopia); nationalism and popular politics; state formation; borderlands; gender, sexuality and ethnicity; and historical methodology and ethnography.

. http://www.somaliaonline.com/the-new-somali-studies-by-safia-aidid/ -

Considering it is against international law for Kenya to order refugees to return home to conflict, what does the Kenyan government think it will do? Concentration camps?

Congrats to Safferz who recently got married

in General

Posted

It was at a place called Hiddo Dhawr in Hargeisa, which is known for its hall built like a traditional aqal Soomaali and the furniture is gambadh etc, and they play kaban on weekends. I've always loved going there for a night out and I find Western-style weddings in Hargeisa really boring. Most brides want nothing to do with Somali culture and wear a white wedding dress and an Indian sari as a second outfit, and the wedding is typically held in banquet halls that look exactly like ones you'd find in Canada or the US.

So I decided I wanted to have a dhaqan wedding just like it would be in miyi, in every detail... down to having a wedding dress made out of subeeciyad (and a xariir dirac later), having the wedding in a hall that looked like an aqal Soomaali, and a traditional galbis to enter. We had buraanbur, a Somali dance troupe that did jaandheer and dhaanto, singers performing qaraami songs with kaban, a cake that looked like subeeciyad, and during dinner we had someone play "askari" and do hal-xidhaale, which was so much fun. But I also love my Somali pop music so at the end we had Maxamed BK and Cabdi Hani perform and turn the place into a hala waasho party lol, how could I have a wedding in Hargeisa and not have my favourite fanaaniin perform!

Life is good walaalo. I completed my research in Ethiopia and I'm currently in Hargeisa writing my dissertation. I should be back in North America in about 6 months, and inshaAllah I'll be graduating with my PhD in spring 2019! How have you (and everyone else) been?

Haha! I appreciate Xabashi culture but I am Somali dee, lol.

Mahadsanid walaal thankfully Itoobiya ma joogo. I was there for the protests and state of emergency late 2015-2016 which was difficult, but this communal violence is much worse.